Leave it to Psmith (1923) was, as far as I recall, the first Blandings story that I read. It was certainly the first Psmith novel I read; I think Mike and Psmith was the last, so that I read his saga more or less backwards.

Here are the opening couple of paragraphs, set in the no-nonsense Intertype Times. This title was first published in Penguin in 1953.

I have written about Psmith before, while discussing Psmith in the City and Psmith, Journalist. I'm not going to reread what I wrote then, but I feel sure I must have spoken of the strange attraction that this scion of Eton and Cambridge has. I am almost certain that I mentioned his appeal lies in his complete anarchist disrespect for the dull and authoritarian. If I did say that, I do think it is important to draw a distinction between Psmith and certain present day public figures in real life who might seem to bear a resemblance. Psmith's highly egged way of speaking has certainly had an influence on a certain generation, and I might safely and without disrespect mention Stephen Fry in this regard. The similarity holds good in his case, because the flamboyant language is there matched by a kind of integrity. In that there is a very stark contrast with Bori….. But no. I mustn't go there.

Leave it to Psmith is a slightly offbeat confection, Psmith being required to fill the role of Wodehousean romantic hero despite the fact that much of his charm lies in his complete indifference to normal emotion. He refuses to be ruffled. He never loses his unique unhinged eloquence. Psmith in love is as unimaginable as Sherlock Holmes in the same fix. However, Wodehouse does somehow makes it work, and with only one or two minor caveats this is a tale brilliantly told, a little masterpiece of the early-middle Wodehouse period.

If I do have one complaint, it is this. As part of the complicated imbroglio, Psmith is at Blandings masquerading as the poet Ralston "Across the Pale Parabola of Joy" McTodd. Psmith is in love with Eve Halliday, an old school buddy of the estranged Mrs McTodd. Psmith maintains his identity as McTodd even in conversation with Eve, and this results in his insistence that the marriage has broken down and that the absent Mrs McTodd is a violent alcoholic. It is an unpleasant and completely senseless lie, where it would have been simpler and sensibler just to say, "I am Psmith. Please keep my incognito." Would Eve really have forgiven him this cruel escapade as easily as she does in the book? Well, she does so, and Wodehouse almost makes it work, so I shouldn't repine.

The story is a variation on Wodehouse's recurring theme of "the theft that isn't really a theft" - though personally I have my doubts about Freddie Threepwood's cheerful assurance that "if a husband pinches anything from a wife, it isn't stealing." The theme goes back as early as Something Fresh (1915) and I wouldn't be surprised if it went earlier; and it goes at least as far forward as Company for Henry (1967) too, if not further. I may return to this fascinating matter at a later date.

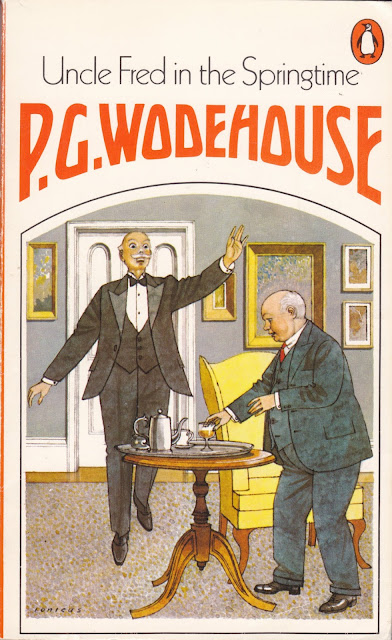

Ionicus pulls out all stops for the cover, as he always did for Psmith. It appears to date from 1975. There is the slightest reminiscence of Joseph Wright of Derby in the single light source illuminating the faces from below. To the right, Psmith (here called Ronald Eustace Psmith, though we know from earlier episodes that he is actually Rupert) is holding forth and in control, as usual. Eve Halliday is appealing and 1920s-ish next to him. To the left are two career criminals, Edward Cootes and Aileen Peavey (prototypes of Soapy and Dolly Molloy from Sam the Sudden and other chronicles), though I'm not so sure Ionicus has made Cootes as tough as I would like. The composition is, as you can see, beautiful.